A Perfect Ending for "Hooked" Almost Came True

Campside Co-founder and Hooked host Josh Dean always hoped that Tony Hathaway’s story would end with him being rehired at Boeing. And it nearly happened.

This is part of Inside the Tent, a series going behind the scenes of Campside’s award winning podcasts.

All episodes of Hooked are available on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

I’m not sure I’ve ever produced a piece of journalism that resonated with people like Hooked did. I’ve made things that were more popular — The Clearing, certainly, or Crime Scene: Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel — but no magazine story, podcast, or documentary resulted in more emails than Hooked, the 9-episode podcast that Campside released, with Apple TV+, in November of 2021. And that has everything to do with the man at its center, Tony Hathaway.

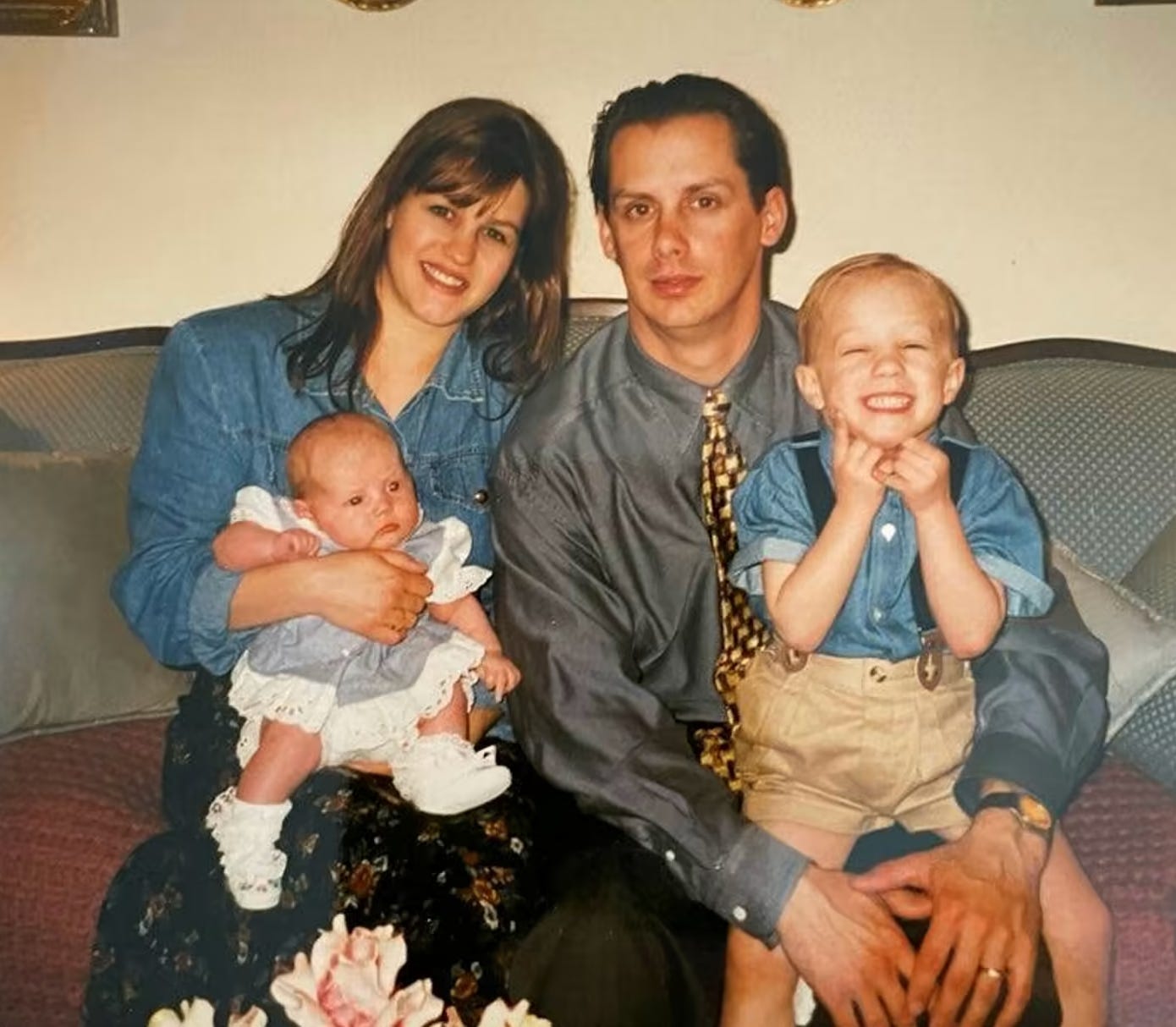

Hooked, if you didn’t listen, told the story of Hathaway, a man from the north suburbs of Seattle who’d been living a version of the American dream — great job, great family, happy life.

That was, until he injured himself in 2008 and was prescribed Oxycontin by his family doctor. You probably know where the story goes from there, in a sense. His life fell apart.

But Tony’s life fell apart in the most spectacular way possible. He progressed from Oxy, to heroin, to heroin with his own son, to a bank robbery with that son (resulting in his son’s arrest), to a mind-boggling spree of 30 bank robberies in just over a calendar year, making him one of the most prolific bank robbers in American history.

Tony’s spree ended at 30 banks, when he was arrested at a bank in the shadow of the University of Washington’s football stadium. That arrest almost certainly saved Tony’s life, and he was sentenced to prison for his crimes. That’s when I first met him, while he was on the back nine of his sentence at a medium security facility. I found him to be humble, honest, and very likable. We started talking, and didn’t really stop, for three-plus years, which resulted in a podcast that laid Tony’s story bare.

He was as open a book as a person can be. Tony made no excuses, owned every mistake, and told his jaw-dropping tale, with all its ugly details. I think, in a way, it was a kind of therapy. I came to really admire Tony, and like many listeners, even rooted for him, which is not a position I often take as a journalist. But it was impossible not to want this man — and his son Conner — to triumph over addiction and heartbreak and to rebuild their lives to show that a second act is possible.

The point of prison is, in theory, to rehabilitate, but too often that’s not actually true. And as anyone who listened to the podcast has heard, Tony and his son really struggled with reentry to society. But as time marched on, and Tony stayed clean and sober, I kept hoping that the ending I had always envisioned for his story — one I used to talk about a lot to my partners on Hooked, Mark McAdam and Elizabeth Van Brocklin — would somehow come true. That Tony could return to the job he had before Oxy. The job he loved and still talks about endlessly: working on airplane design for The Boeing Corporation.

Before the accident, and the Oxy, Tony had been a senior engineer in the galley systems group, designing kitchens for jumbo jets at the Boeing factory in Everett, which is one of the largest buildings on the planet. Even more impressive: Tony was the only engineer at his level without a college degree. He had started low, with just a high school diploma, and worked his way up to a big job at one of America’s most important companies. And he LOVED it there.

Boeing, like Tony Hathaway, has struggled quite a bit over the past decade. The company needs some positive news coverage at this point about as much as he does. So I always thought it made sense for Boeing to hire him back. And I hoped someone at Boeing might hear the podcast, listen, and want to do something bold — something that would inevitably result in a great PR story for Boeing to tout. They could allow Tony’s redemption arc to come full circle.

Tony hoped for this, too. Almost from the minute he got out of prison, he began applying for jobs at Boeing. He was happy to start low again, and work back up. He wrote letters and worked every connection. He learned that Boeing did hire felons and began to hope. He even had plans for what he’d do once he had a little money again. He and Conner wanted to open a residential recovery facility for people in the Seattle area struggling with addiction and homelessness. They were calling it Project Hope. And I could hear the hope in Tony’s voice when he wrote to me about it in the fall of 2023. “If I can land a job at Boeing and get this non-profit off the ground, we'll be on our way back, no bank robberies required!” he joked.

Then, a few months later, Tony sent even better news. He’d gotten a series of interviews at Boeing, and was on the verge of a job offer in the engineering department. He’d been completely honest with them. He had no choice. “I told them everything, starting from the beginning,” he told me, “but finally at one point one of them stopped me and just said, ‘That’s enough.’”

And it apparently worked, because Tony did get a job offer. He was ecstatic, and I felt so happy for him. There was just one final hurdle: the background check.

You can probably imagine where this is going.

Like many companies, Boeing outsources its background checks to a third party firm. Obviously, this company was going to find Tony’s voluminous criminal record. But he’d been completely honest with the team that hired him. So I assumed this wouldn’t be a problem. I assumed wrong.

On March 7, 2024, I got a note from Tony. “My background check came back last week, reflecting my felony convictions,” he wrote. “They're considering withdrawing the offer.” He was given a chance to “explain the circumstances surrounding my convictions,” and asked if I could write him a letter of recommendation. I was happy to.

It didn’t work. And by late March, the offer had been officially rescinded. Hooked wouldn’t get that storybook ending I’d been imagining — at least not yet. “No second chances at Boeing,” he wrote to me. “I'm disappointed, but not surprised. What really pisses me off is that I know without question, with 21+ years of Galley Engineering experience, I'm the most qualified applicant for that job requisition. Feels like discrimination in a sense.”

Tony also shared with me the responses he’d written to the company, including this tragic summary of his catastrophic fall: “Around 2008 I suffered a back injury and was prescribed the painkiller OxyContin by my family practitioner. I had 2 back surgeries over the next few years and became chronically addicted to a medication that I was told was not addictive.

It destroyed my life. I lost everything, my career at Boeing, my house, my car and all of my possessions. More importantly, I let my family down, my friends and my colleagues. I made some terrible choices to support my addiction. I wish I could take it all back, but I can't. I accept responsibility for the choices I made, have served my time and am working hard every day to make amends.”

Tony explained that he’d been released from prison just two months before the COVID-19 pandemic shut the world down – just about the worst time possible – and that he’d been unable to find any good work since. And yet, he hadn’t relapsed. “I haven’t had as much as a parking ticket,” he wrote.

Tony had helped his son Conner stay clean and find work, in part by being a caregiver for Anthony Jr, Conner’s son before school and during holidays. For more than two years, the three of them shared a small apartment, and lifted each other up, even in the face of relentless setbacks.

“How do I redeem myself and make amends if nobody is willing to give me a second chance?” Tony wrote. “And while I understand the seriousness of my convictions, I ask that you strongly consider my 21+ years of employment at Boeing. Review my personnel file and performance reviews. Take into consideration the fact that the crimes I committed 10 years ago were directly linked to my addiction to pain medication that was prescribed by my family doctor. I've been clean for over 10 years now.”

The last part of Tony’s response really stuck with me: “I was released from prison just over 4 years ago and have done everything within my control to be a good role model to my kids and grandkids. The only thing I've failed at to this point is finding meaningful employment.”

“This wasn't supposed to be a life sentence.”

Anyone who’s listened to the podcast won’t be surprised to hear that Tony still isn’t giving up. He’s appealed to the engineers’ union for help, and is planning to work political channels to try and investigate whether Boeing really does hire felons, and under what circumstances. He still hopes that, somehow, the right person will hear his story and do the right thing.

Maybe that person is reading this now?

Thanks for reading. For more on Tony Hathaway and Hooked, subscribe now. There are plans underway for new material that will appear both in the Hooked feed and here.

Josh